What do DMEK and DSAEK stand for, and what is the difference between these two transplants?

DMEK stands for Descemet’s Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty and DSAEK stands for Descemet’s Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty. The names can be confusing. Both surgeries involve first stripping out the patient’s (host’s) old Descemet’s membrane and corneal endothelium.

DMEK is more selective than DSAEK. Both DMEK and DSAEK remove Descemet’s membrane and endothelium. DMEK adds only a new Descemet’s membrane and endothelium. DSAEK also adds a new Descemet’s membrane and endothelium but with a layer of donor stroma. A way to remember this is to pretend that the “S” in DSAEK stands for “stroma.” The “automated” in DSAEK really just refers to the automated device that cuts the thickness of the donor cornea.

The difference between DMEK and DSAEK can be explained with a wallpaper analogy. Let’s say your wall needs new wallpaper. In both DMEK and DSAEK, the old wallpaper is removed. With DMEK, only new wallpaper is inserted. With DSAEK, a new piece of drywall that has new wallpaper on it is inserted on top of the old drywall.

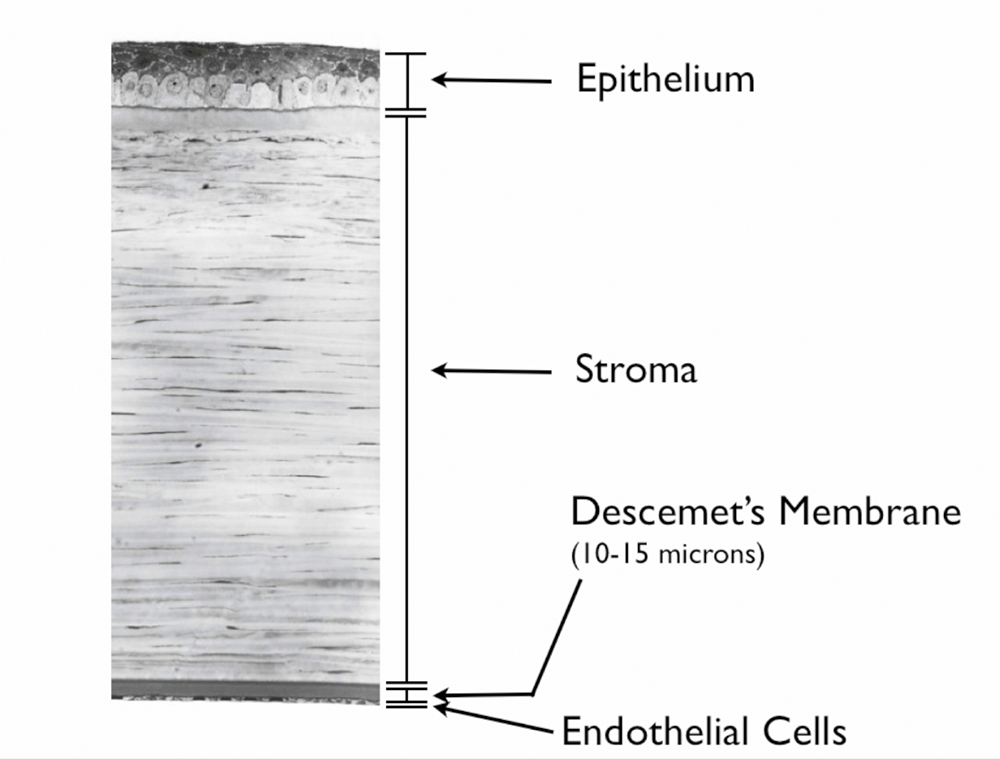

The image below label the different layers of the cornea.

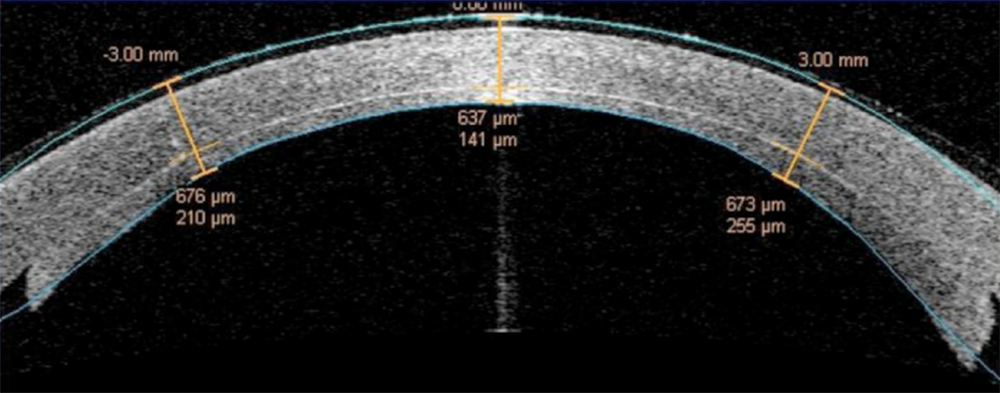

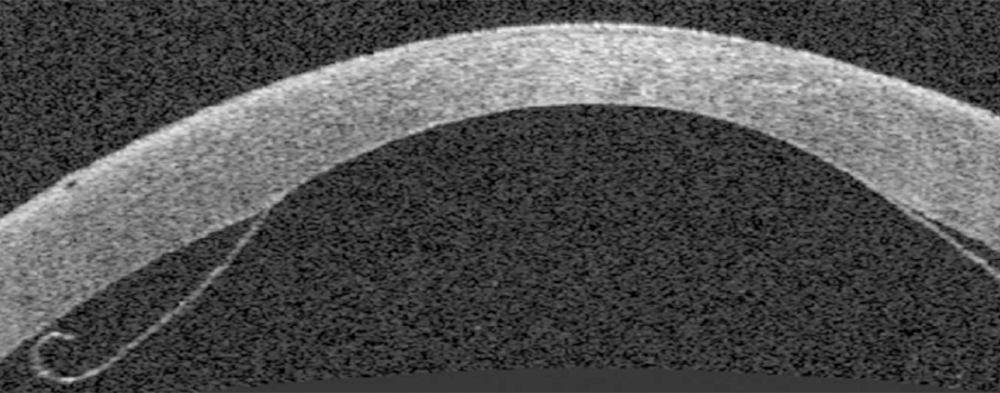

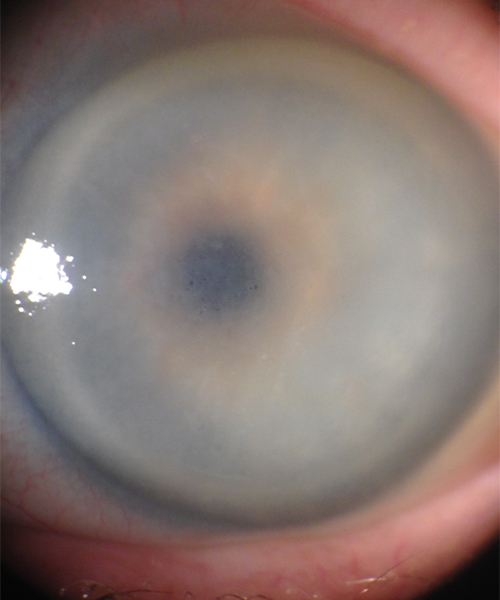

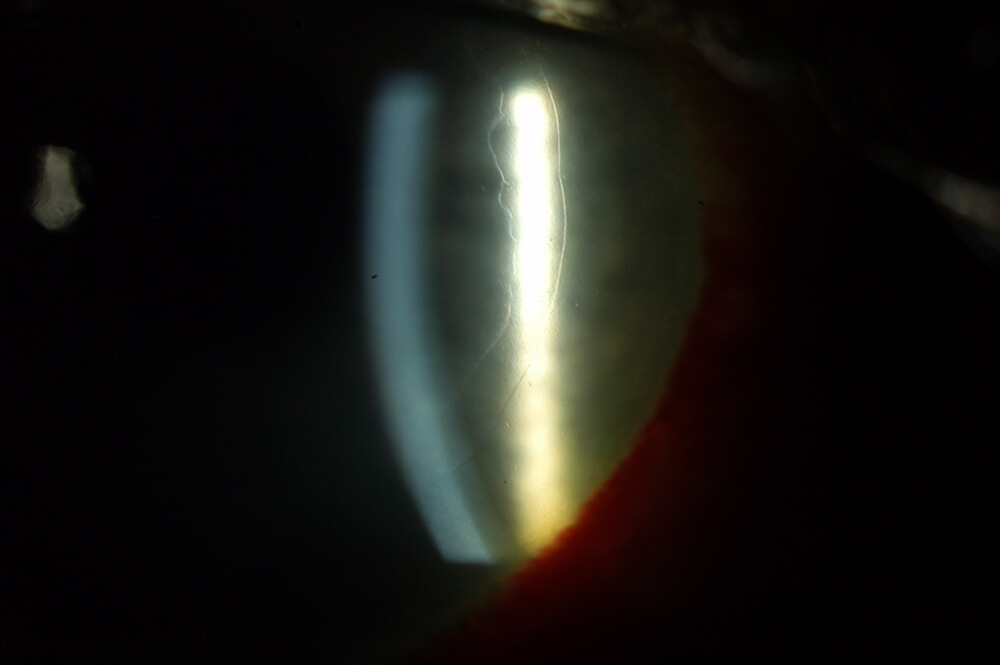

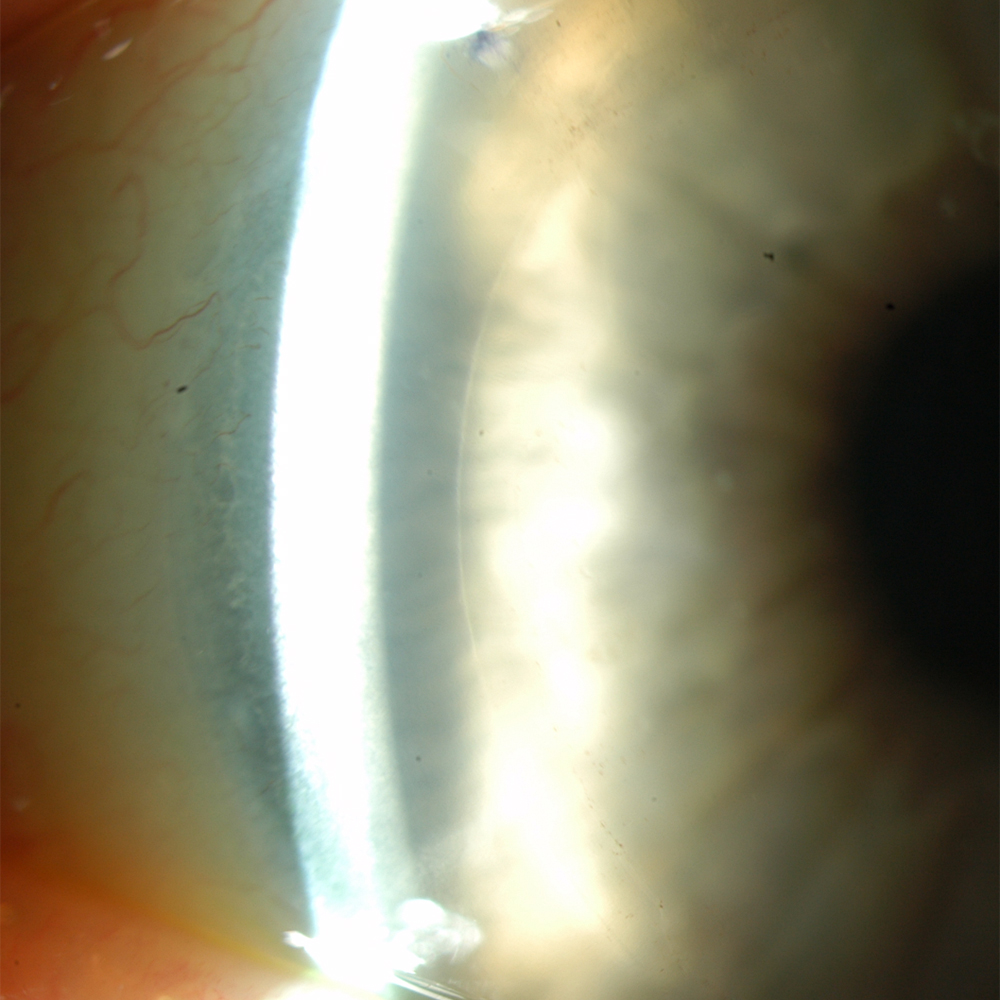

The next images show DSAEK and DMEK transplants. Notice how easy it is to see the DSAEK transplant in the eye, because it has a layer of stroma with it. DMEK is almost impossible to see unless it is not fully attached yet. This image of a partially separated DMEK is shown here just so that you can appreciate how thin the graft is when no stroma is transplanted. You can see how important these grafts are to the cornea, because any area that doesn’t have the graft attached will swell thicker than other areas of the cornea.

This images above were taken with an office examining scope. The image on the left shows the tremendously blurry view of a patient’s cornea before DMEK by Dr. Tenkman. It was even difficult to appreciate her iris details. The on the right is 2 weeks after DMEK by Dr. Tenkman. Her vision was 20/15. The patient could see much better out of her eye, but notice how much easier it is for us to see in and appreciate her iris details. At first glance, one would never know that this eye had a DMEK. A special light technique below allows one to see the DMEK.

What are DMEK and DSAEK used for?

DMEK and DSAEK are used to treat blurry vision due to disorders of a patient’s corneal endothelium. They involve removing a patient’s diseased Descemet’s membrane with the endothelial cells that live on it, then transplanting a new Descemet’s membrane and endothelium. If a patient has severe opacification or scarring of the corneal stroma, it may be necessary to transplant more of the cornea with a full-thickness Penetrating Keratoplasty (PK) transplantation.

In the age of selective keratoplasty, PK is contraindicated for strictly endothelial disease unless there are extenuating circumstances that would prevent the success of DMEK or DSAEK. The corneal endothelium can become sick and in need of replacement due to genetic disease (Fuchs endothelial dystrophy, posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy, etc), inflammatory or autoimmune disease (iritis, endotheliitis, etc), trauma, or prior intraocular surgeries.

We all lose corneal endothelial cells throughout life. Since most of us are born with an excess of corneal cells, we typically don’t run out of them. If a person suffered an insult to their corneal endothelium at one point, gradual loss of endothelial cells can eventually lead to corneal swelling and poor vision. Thus, the symptoms often seem to develop gradually over time. Click here for the symptoms and mechanism of early corneal endothelial decompensation in Fuchs.

What is the difference in effect for DMEK & DSAEK?

DMEK provides better vision (average is 20/20 with some better and some worse), faster recovery (average is 2 to 4 weeks), and less rejection than any other type of corneal transplant (< 1% rejection in first 2 years). DMEK can also be combined with Toric IOLs so that cataract patients with corneal astigmatism can hope to be glasses-free. Dr. Tenkman has several patients who required glasses preoperatively due to astigmatism who see 20/15 in each eye without glasses following DMEK. Dr. Tenkman’s mother used to have Fuchs Corneal Dystrophy. Dr. Tenkman prepared both of her donor’s. He inserted the donor for one of her eyes and his mentor, Francis Price Jr., inserted the donor into her other eye. Both of her eyes now see 20/15 (one line better than 20/20) and she has excellent cell counts. DMEK also is the only cornea transplant that can regularly be used with multifocal intraocular lenses during cataract surgery, and we have many such patients.

The results of DSAEK are not as good when compared with DMEK. Average vision is about 20/30, recovery is 3 to 6 months, the rejection rate is 5 to 12% depending on how thick the transplanted tissue is, and it cannot be used in conjunction with astigmatism correcting lenses in cataract surgery. Presumably, the vision is not as good because of the extra stromal tissue along with the interface between the host and donor stroma tissue.

The increased rejection rate in DSAEK is also likely caused by the extra stromal tissue. White blood cells contained in the host stroma can freely travel into the donor stroma with no barrier blocking them. Once there, the white blood cells encounter foreign transplanted cells and can mount a rejection response. In contrast, all foreign cells in DMEK are hidden on the other side of the new Descemet’s membrane where the host’s white blood cells cannot find them.

The recovery rate is slower in DSAEK because the transplant’s cut edge has no Descemet’s membrane on it. The barely exposed stroma is easily hydrated by the fluid in the eye creating corneal swelling. This swelling takes months to go away and does not resolve until new Descemet’s membrane grows onto this cut edge. With DMEK, by contrast, all the stroma is covered by Descemet’s membrane from day 1 so the corneal swelling goes away more quickly.

Astigmatism is unpredictable with DSAEK since the thicker graft carries some unmeasurable amount of astigmatism with it. Thus, calculations for proper astigmatism correcting lens cannot be made before cataract surgery.

Click here for an overview of the various types of corneal transplantation surgery.

How often does the air have to be reinjected in DSAEK & DMEK to help fully attach the donor?

In experienced hands, DSAEK air reinjections are only required 1% of the time. Partial separartions of DSAEK donors almost always seal down fully on their own. In the paset, DMEK required air reinjection 25-30% of the time. Eventually, DMEK surgeons have realized what types of DMEK partial separations are likely to seal down on their own. This combined with using longer lasting air mixtures has allowed us to reduce the air reinjection rate down to about 1%… just like DSAEK.

Why don’t most corneal surgeons perform DMEK?

Most corneal surgeons perform DSAEK instead because they find it easier to do. There are some corneal surgeons who don’t even perform DSAEK and still offer the far more invasive penetrating keratoplasty (PK) for purely endothelial disease. The challenge with DMEK was to devise a technique to peel the Descemet’s membrane and endothelial cell layer from a donor without tearing it, then insert it into the patient’s eye, uncurl it (the tissue wants to curl up naturally), and attach it… all while minimizing any direct touching of the donor since any touch kills some cells. Many thought such techniques would never develop. Thankfully they have, so with proper training and in good hands DMEK provides patients a minimally invasive way to restore vision.

What have we done to advance DMEK surgery?

Our surgeons helped to pioneer several DMEK techniques, including those to advance DMEK donor prep. If a donor is lost during preparation, which is done before the patient’s surgery, the patient’s surgery would need to be postponed. The published donor loss rate during attempted DMEK preps was historically about 20%. Dr. Tenkman pushed this donor loss rate far below 1% as a fellow which lead to a publication in Cornea (click here to view paper) and has since reduced his private practice loss rate to 0.04% (1 in about 2,300). Dr. Tenkman discovered donor horseshoe tears, “smile configuration,” and other challenges, and developed techniques to handle these DMEK donor prep difficulties. Dr. Tenkman also helped pioneer techniques to implant DMEK donors inside the patient’s eye: how to unlock point lock folds, how to gently flip a donor out of taco configuration by using gentle bursts of fluid. Many of these techniques allow us to successfully perform DMEK in eyes that other DMEK surgeons would think challenging or not possible, including eyes with prior glaucoma surgery or tubes, eyes with prior anterior chamber intraocular lenses, eyes with previous PK transplants, and eyes with prior vitrectomy.

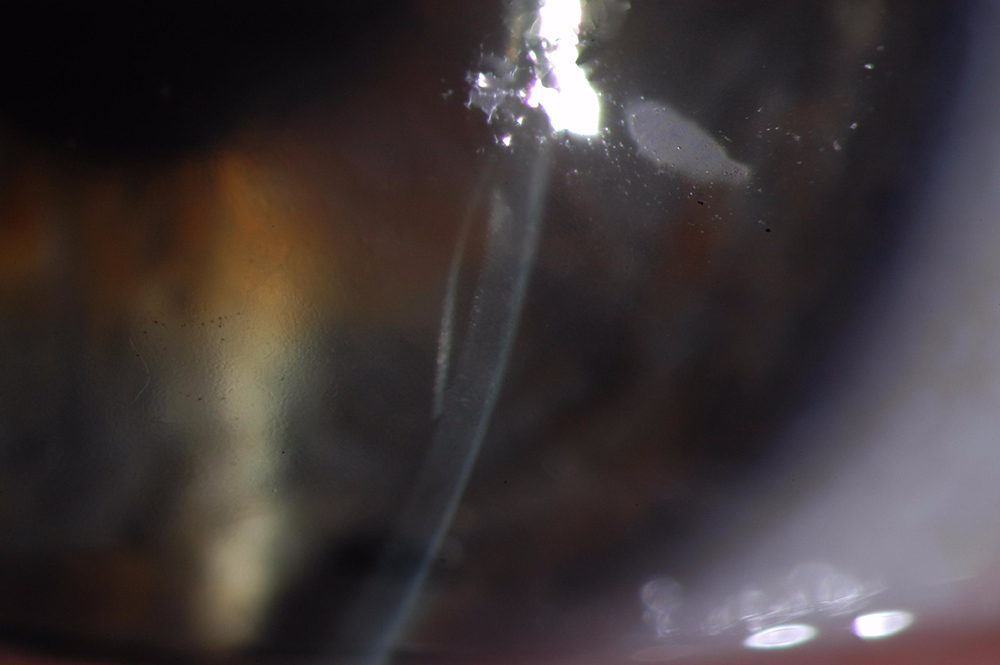

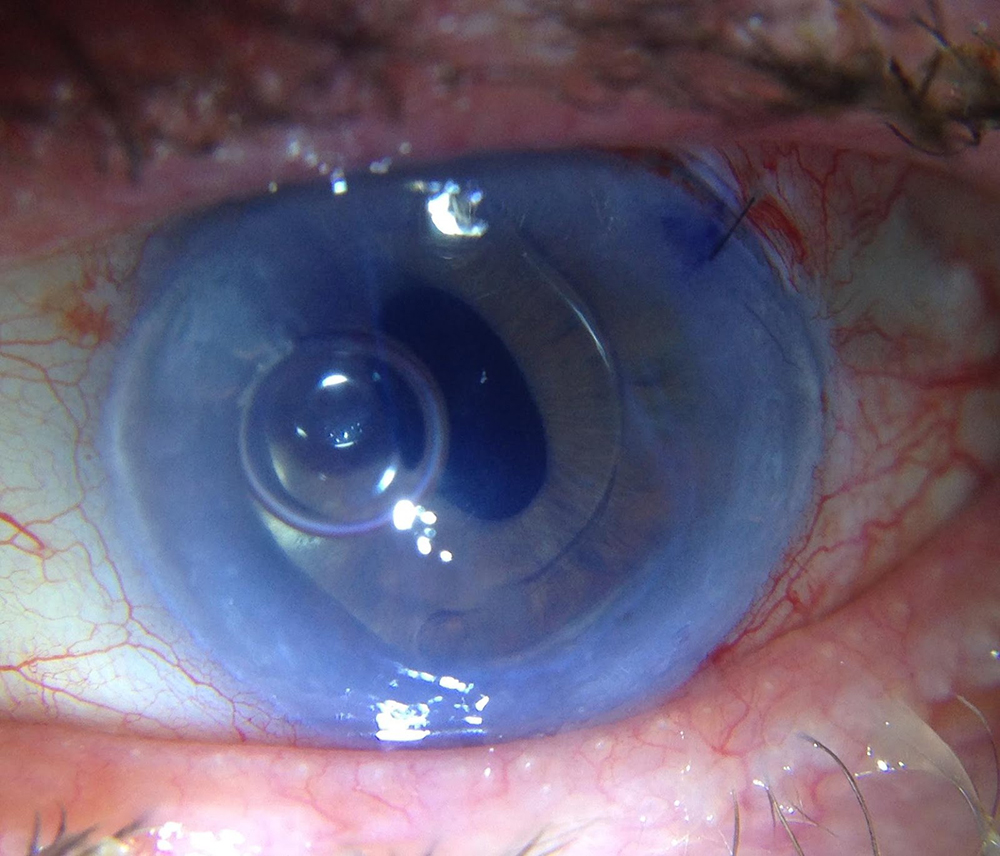

Below is a picture from 2014, one of the first very difficult DMEK cases Dr. Tenkman performed. This photo is less than 24 hours after surgery. This patient had only one seeing eye and was afraid of surgery, so he waited so his cornea was almost impossible to see anything through before having his surgery. Most surgeons would consider surgery difficult if a patient had any of the following: a glaucoma tube, an anterior chamber IOL, a large iris defect, prior vitrectomy, a very difficult view through the cornea, and severe glaucoma. This patient had all these things in his only seeing eye. The surgery was successful and restored the patient’s vision. Prior to surgery, the patient’s iris details and lens in front of his eyes wouldn’t have been distinguishable on a photo like this. Due to special medical considerations in this case, Dr. Tenkman took this photo in the patient’s car with handheld instruments while the patient reclined so that he wouldn’t have to come up to the office and sit upright for a prolonged period of time (part of what allowed this incredibly unique case to be successful).

To date, all of the eyes that we’ve attempted DMEK on have been successful. Less than 1% of the time, our initial DMEK surgery had to be repeated due to rejection or other problems, but all repeats to date have been successful.

Should my surgeon ever chose DSAEK over a DMEK?

As mentioned above, most cornea surgeons do not perform DMEK. It requires more practice and experience. Although we may still select DSAEK for very specific cases, we typically recommend DMEK for most patients.

Is DMEK guaranteed to make me 20/20?

No. The average patient sees some or all the letters on the 20/20 line. Some see better and some see worse. Even if the cornea is perfect, a person might not see 20/20 because of imperfections elsewhere in the eye. The same is true with “perfect” cataract surgery. Every eye has different potential. We will inform you of any other problems that may limit your final vision before surgery when possible.

Are steroid drops needed life-long after DMEK or DSAEK?

Studies from Price Vision Group have proven that long-term rejection episodes are less likely if the patient at least maintains low potency steroid drops once a day. That being said, it would be safe to closely watch patients without steroid drops if they have trouble tolerating the drops. The rejection rate after stopping steroid drops long term for DMEK is estimated at about 6%.

Do I have to worry about my DMEK or DSAEK ever “falling off” the back of my cornea? How long will my transplant last?

We watch you close after surgery to see that the attachment process is successful. This process CAN take a few weeks to complete. Once the donor becomes ONE with your cornea, it can not “fall off”.

Traditional full thickness corneal transplants last about 20 years (give or take depending on the disease type). Cell count studies show that, with the passage of time, transplants still lose endothelial cells gradually like any other cornea, but usually at a faster rate. When the endothelial cell counts fall low enough, the transplant “fails”. Since DMEK and DSAEK are relatively new, it is not possible to say how long they will last; however, preliminary data is encouraging, especially for DMEK. There is variation between transplants, but early data suggest many transplants will last one’s lifetime. Either way, replacement is possible.

We are studying variables that may reveal which donors have have cells that are more resistant to death and also surgical techniques are minimally harmful to endothelial cells. Many surgeons suggest it is normal to lose 30-50% of the donor’s endothelial cells during surgery. Dr. Tenkman has some early data suggesting less than 10% cell loss from surgery when selecting a specific subset of donors.

BY OPTING FOR A DMEK OR DSAEK PROCEDURE, YOU ACKNOWLEDGE THE FOLLOWING:

The success of your DMEK (or DSAEK) requires your participation. These rules aim to help your donor attach as fast as possible.

- Rule #1: No eye rubbing! Any pressing on the eye could slightly indent the cornea and make a portion of the donor detach from your cornea. A protective shield needs to be worn at night so you don’t accidentally rub your eyes for 1 month or until 2 weeks beyond the time that your surgeon notices your transplant is “100% attached” (whichever is longer)

- Rule #2: No forceful blinking the night after. A strong blink can be considered a “soft rub” or the eye. Even though the drops may burn some, make a conscious effort not to blink forcefully… just gently.

- Rule #3: Look at the ceiling. On the day of surgery, the only thing that will keep the donor in place is the air bubble inside of your eye (no stitches). The air actually functions to hold all the fluid away (you don’t want micro-currents from the fluid in the eye “rinsing” the new wall paper off!). It is important to keep the fluid away while the donor secures a firm attachment to to your cornea. The air only lasts a several days and the bubble gets smaller as time goes on. Air rises, so every time you stand up and look straight ahead or down, the bottom of your donor is “underwater”. When you lay flat and look at the ceiling, this makes the cornea the “ceiling” of your eye so that the air bubble can rise up and protect the whole donor. For DSAEK, you likely only need to lay the first day. DMEK needs more “air time”, so we use the first 2-3 or more days. When “longer lasting gas” is used, which is the most modern technique, only 1-2% of eyes need to have an “air reinjection” due to dificulty attaining attachment.

- Rule #4: You have to stand up from time to time (bathroom, eating, etc). We don’t want you to lay flat for days straight (we don’t want you to get a blood clot). Get up 5-10 minutes every hour or two on average. You will have to be up longer when eating or using the restroom.

- Rule #5: Call with problems. Because of the air bubble in your eye, on the day of surgery there is a risk this flow of fluid could be blocked in the eye and cause high pressure, which can harm vision. That’s why we always check the next day. But if you get a major headache over your eye or eyebrow with nausea, be sure to call us because we may check you sooner. The “laser treatment” we give before surgery almost always prevents such pressure spikes, but they still are possible and we sometimes have to release a little of the pressure.

- Rule #6: Take your drops as instructed.

- Rule #7: You cannot fly until the air bubble is gone. This is usually 7-14 days after surgery. It can be longer, so inform your surgeon if you plan to fly in the first month after surgery.

- Please do not hesitate to call with any questions.