Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy (FED)

Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy (FED) is a genetic disease of the cornea. Early on it causes mild blurry vision, while in its advanced stages it causes severe vision loss and pain. The goal is to treat the disorder with DMEK transplantation somewhere between the onset of noticeable symptoms and severe disability. If allowed to progress to the point of chronic scarring, the disease isn’t fully treatable with DMEK, and more invasive procedures like PK must be used. PK has far more risks and negatives than DMEK and doesn’t give anywhere near the visual results.

What is Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy (FED)?

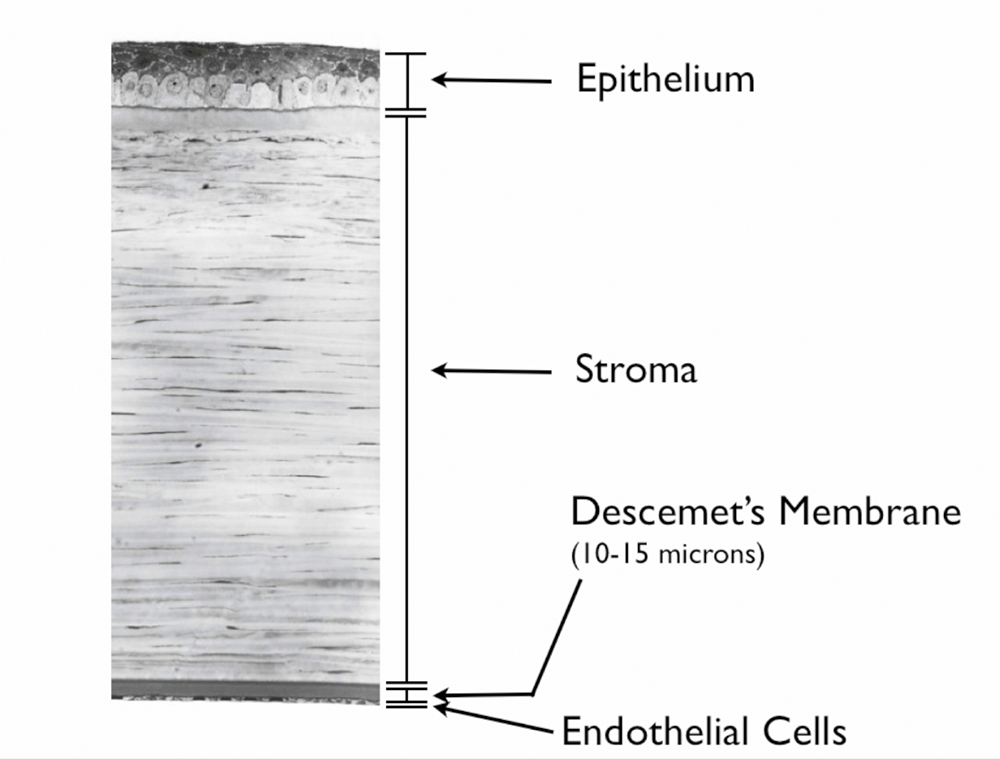

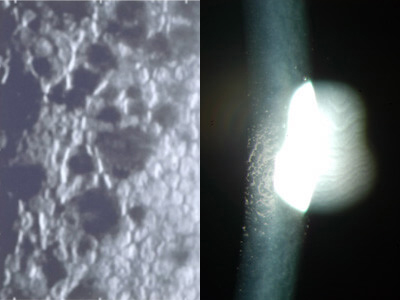

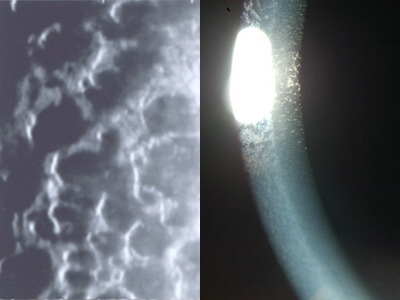

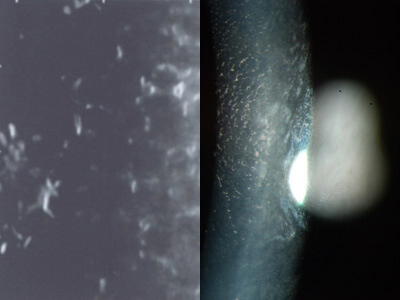

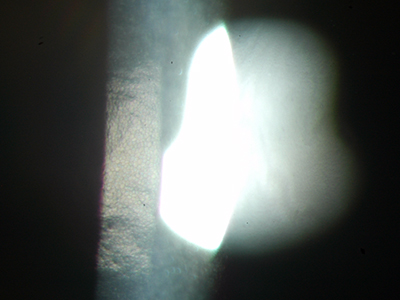

FED is a genetic disorder where the inner layer of the cornea is sick and leads to blurry vision. The cornea is the clear window in the front of your eye. The inner layer of the cornea is lined by tissue, Descemet’s membrane (DM), that is as thin as Saran wrap. This membrane has special endothelial cells that live on it whose job it is to keep the cornea clear. In FED, the DM becomes irregular and distorted (guttata deposition) while the endothelial cells die off and can’t do their job. Over time, the cornea becomes swollen and foggy. When the disease is about to really “go over the cliff” and scar up one’s cornea, the patient will vision is worse immediately upon waking. Soon after this, the “morning fog” starts to last later and later into the day, and can be followed by severe corneal scarring.

When does Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy (FED) affect a person? What are the symptoms?

On average, FED affects vision mildly in one’s 50’s, and increasingly more severely into one’s 60’s and beyond. But those are only averages since some cases are severe as early as one’s 30’s while others can be mild into one’s 70’s. Genetics may play a role in this variation. In the early stages, FED blurring is mild and is only due to the distortion of DM by guttata. As time goes on, blurring progressively worsens. This is not only due to worsening guttata but also from the development of corneal swelling (edema). Corneal edema tends to be the worse in the morning and improves some later in the day. The blur that is solely caused by guttata or swelling improves fully with DMEK surgery. Eventually, FED can “go over the cliff” and the cornea can “decompensate”. Decompensation may be gradual or sudden. Decompensation is common after cataract surgery (ie, the irritation from surgery can be the “last straw” and put the cornea over the edge). A decompensated FED cornea becomes severely swollen, and painful blisters may form on its surface. These blisters are one of many things that can irritate the eye surface to make it feel like there is something is in it. An exam by your doctor is necessary to tell if such foreign body sensation is truly due to severe swelling and blisters. Swelling that is severe enough or goes on long enough can result in permanent corneal scarring (fibrosis). Patients with severe scarring need a full corneal thickness penetrating keratoplasty to see better.

Where does the swelling come from in Fuchs Corneal Dystrophy?

To understand where the swelling comes from, you need to understand the fluid inside the eye. The cornea and other parts of the eye have no blood flow but need oxygen and nutrients like any other part of the body. Rather than allowing blood vessels to course through the cornea or blood to fill the eye, which would block vision, the eye has another solution. Arteries hyper-filter the blood to produce a clear fluid inside the eye called aqueous. Before exiting the eye through veins, this fluid flows into the cornea to deliver oxygen and nutrients. The fluid causes the cornea to swell just a little. A tiny bit of swelling and moisture is okay, but too much makes the cornea hazy which blurs vision. The corneal endothelial cells continually pump the old fluid back into the eye to make room for new fluid and to prevent the cornea from becoming swollen and blurry. Because the endothelial cells in Fuchs are dying off, they can’t do their job so fluid builds, causing the cornea to swell and become hazy.

What is the mechanism by which vision is worse in the mornings for decompensating Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy (FED)?

Having your eyes open while awake helps some of the excess corneal fluid escape via evaporation. While closing your eyelids all night long, the endothelial cells get no such help and can get behind by morning. The cornea, therefore, is swollen and hazy when you wake up, causing your vision to be blurry. Once you wake and open your eyes, evaporation helps the endothelium catch up. When enough cells die off, evaporation is not enough to clear the cornea by itself, so during full decompensation, the cornea stays severely cloudy all day.

Can we predict when surgery will be needed for Fuchs Corneal Dystrophy?

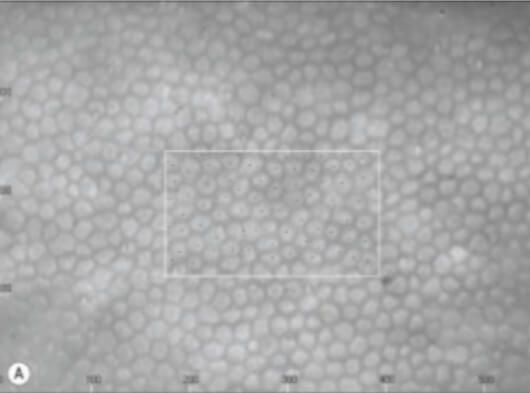

There is a range for how quickly the disease progresses. A lot of this is genetic. A special camera, specular microscopy, can count the endothelial cells to see how quickly a patient’s disease is progressing from visit to visit. This picture and clinical exam data can give some suggestion of disease progression. However, more sudden worsening and progression of FED is still both possible and unpredictable.

What is the treatment for Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy (FED) and when is surgery recommended?

Old forms of treatment were aimed at dehydrating the cornea. These included concentrated salt water drops (Muro 128) or blowing a hair dryer across the eye surface. These treatments are outdated since, if FED is advanced enough that the cornea is starting to swell with morning blurriness, then DMEK should be considered soon to prevent fibrosis. Not that long ago, only full thickness transplants (PKs) were available. Because PKs have a lot of negatives and limited positives, surgeons would try to delay surgery as long as possible with Muro 128 or hair dryers. The definitive treatment for FED is corneal transplantation. In the DMEK era, the ideal timing of surgery is to wait until a patient is symptomatic but not until they are so symptomatic that they have permanent stromal fibrosis. Ideal timing allows the best long term vision and can restore the cornea to normal.

What are the types of transplants are available for FED?

Click here for an overview of the various corneal transplant surgeries. The best cornea transplant for FED by far is DMEK. DSAEK, the predecessor of DMEK, is inferior in many respects. PK was the first type of transplant developed in the early 1900s. Although PK is useful for some conditions, it is absolutely not the ideal treatment for FED and is only used for where severe stromal fibrosis has occurred that requires the removal of corneal scarring.

How have cornea transplants for Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy (FED) advanced through the years?

- Penetrating Keratoplasty (PK). PK is a full thickness corneal transplant. Endothelial disease was traditionally treated with full thickness transplants where a circular cookie cutter-like blade cut out all layers of the patient’s cloudy cornea. The donor cornea was cut in a similar way and the transplant button was moved over to the patient and sewn into place. To understand PK, think of a room where one of the walls has sick wallpaper. To get new wallpaper, a PK knocks out the entire wall and brings in a new wallpapered wall. Stitches remain in place for a year, and visual recovery typically takes a year or more. Even if the stitches are sewn perfectly, high astigmatism (irregularly shaped cornea) often develops. Because of irregularity, one-third of full thickness transplants need a hard contact lens to achieve the best vision. For full thickness transplants, the average best vision with glasses or contacts is 20/30, the rejection rate is 16% in the first 2 years and the recovery time is 1 year. Such a large incision increases the risk of losing one’s eye during surgery. It also increases the risk significantly that the eye could rupture with blunt trauma years even years later. Because of these and other limitations, surgeons don’t do PK for strictly endothelial disease.

- Descemet’s Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSAEK). This is a form of a partial thickness cornea transplant. In the early 2000‘s, corneal surgeons were looking for a way to replace endothelial cells without replacing the entire cornea. An early form of partial thickness transplantation was DSAEK. In DSAEK, the patient’s sick Descemet’s membrane and endothelial cells are peeled out in one piece. Then, the back one-third to one-fourth of a donor cornea is stuck onto the back of their cornea. The DSAEK donor contains more than just Descemet’s membrane and endothelial cells; it also contains a significant amount of the middle stroma layer of the donor cornea. To use the wall analogy from above, in DSAEK the sick wallpaper is stripped out, and a new piece of drywall with new wallpaper on it is brought in and put over the top of the old drywall. With DSAEK, the average best vision with glasses is 20/30, the rejection rate is 5 to 12% in the first 2 years, and recovery time is 3 to 6 months. 20/20 vision with DSAEK is not common. It seems that this excess stromal tissue from the donor prevents excellent postoperative vision.

Descemet’s Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK). This is a form of a partial thickness corneal transplant and is the most perfect solution for FED. Using the wall analogy, the old sick wallpaper is removed and nothing but the new wallpaper is inserted. A one for one exact switch. DMEK provides better vision (average is 20/20), faster recovery (average is 1 month), and less rejection than any other type of corneal transplant (< 1% rejection in first 2 years). Dr. Tenkman has shown that DMEK can be combined with Toric IOLs so that patients with corneal astigmatism can hope to be glasses-free and that DMEK eyes can receive multifocal IOLs. He has several patients, who required glasses preoperatively due to astigmatism, who see 20/15 in each eye without glasses following DMEK.